For many small direct-to-consumer brands, expanding into brick-and-mortar retail is a pivotal moment.

Plenty of brands are continuing to invest in running their own stores, especially after restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic were lifted.

In the past month, hair care brand Cermonia opened its first permanent store in the SoHo neighborhood of New York City, clothing brand Tentree opened its first space in Washington, D.C., and Reformation and On expanded their existing footprint with new stores.

But opening physical stores can prove to be just as much of a company’s downfall as it is a lifeline.

Such was the case with DTC sleepwear brand Lunya, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on June 16.

Los Angeles-based Lunya is focused on selling men’s and women’s sleepwear, with its top-selling products made of washable silk material. The brand’s pricing is premium, with its washable silk cropped tee coming in at $128 while its cami pant set costs $248.

Court documents from the brand’s Chapter 11 filing show how trends from the COVID-19 pandemic uplifted the brand, with its gross revenue peaking in 2020 and 2021 at $50 million.

But the impact COVID-19 had on consumer demand in Lunya's sector quickly went away. The company’s CEO Blair Lawson said in its bankruptcy declaration that multiple trends that helped push its growth have now experienced a “complete reversal,” leading to declining revenue.

Here is a look at what brought Lunya to bankruptcy, and how much its venture into physical retail cost it.

A mountain of issues

Lunya was founded by entrepreneur Ashley Merrill in 2012 and launched formally in 2014 with a focus on “thoughtfully designed” sleepwear. The company used to run a separate men’s brand, called Lahgo, but merged the businesses in 2022.

Lawson said in the company’s bankruptcy declaration that Lunya sold exclusively through its online website for five years before it grew rapidly in 2019 and 2020.

The main factors contributing to its fast growth were: a “massive increase in demand” for lounge and sleep apparel stemming from COVID-19; a bump in e-commerce demand due to the pandemic; and “highly efficient” customer acquisition from ads on Facebook and Instagram.

However, those trends have since fully reversed, impacting the business’ performance. Demand has lessened for the category, despite Lunya placing bets that its rapid growth would continue, and Apple’s iOS 14 update proved catastrophic to the brand’s ability to target advertisements. Such advertising on Facebook and Instagram had been Lunya’s “primary source of new customers and revenue.”

Lawson — who joined the brand in May last year — notes that prior to making significant changes to the business in 2022, Lunya had been placing orders with its manufacturers for most of its finished products nine to 12 months prior to delivery.

Wrongly expecting the same level of growth it had gotten in 2019 and 2020, Lunya in 2020 ordered about 60% more inventory than was ultimately needed to support 2021 sales.

In addition to Lunya facing a shift in consumer patterns and declining advertisement results, Lawson said that the brand’s finance and operations leadership from 2020 to 2022 “lacked some specific experience in e-commerce, retail and inventory management.”

This resulted in a series of factors which only increased the brand’s existing problems, including high third-party logistics costs and a buildup of mismanaged inventory.

Under such leadership, Lunya also attempted to diversify its distribution channels by investing heavily in brick-and-mortar — a decision that would come at a steep price.

The ‘drag of the unprofitable retail stores’

A majority of the brand’s revenue comes from its e-commerce channel, which made up 83% of its $35 million revenue in 2022 — a 30% decline in revenue from its peak of about $50 million the year before.

Lunya entered into several retail leases — in locations such as San Francisco and Los Angeles — that were too expensive and large for the business’s size. Lunya lost about $135,000 every month on average for the past year on its physical retail network.

Owned retail stores — of which the brand had seven — and wholesale each made up only 8% of last year's revenue. The company’s website currently lists just three retail locations. Lunya did not respond to inquiries from Retail Dive about the closures.

Additionally, the company’s finance team wasn’t closing Lunya’s books on a timely basis, meaning that the brand “did not have a clear and accurate weekly cash flow model, resulting in a chronic lack of visibility to monthly performance compared to budget and, more important, cash flows and projections.”

Lawson has implemented a number of strategic changes over the past year that improved EBITDA losses, including expanding its wholesale distribution and reducing investment in seasonal products. Under Lawson, Lunya also reduced its corporate workforce from 46 full-time employees to 28 as of June.

However, the “drag of the unprofitable retail stores” remains, and Lunya is still unable to pay its vendors, pushing it into bankruptcy. The company has no secured funded debt, but owes a third-party logistics provider about $500,000 and has about $6 million of unsecured debt that consists mostly of trade and credit card debt.

As part of its bankruptcy, Lunya has submitted a request to the court to reject leases and executory contracts with companies including Leap, a retail platform helping DTC brands enter brick-and-mortar retail. The request impacts leases in Atlanta, Houston and San Francisco, as well as contracts in cities like Chicago.

According to the rejection request filing, Lunya has “ceased all operations” at the spaces related to the leases with Leap. Lunya added that the leases and contracts “constitute an unnecessary drain” on the company’s limited resources.

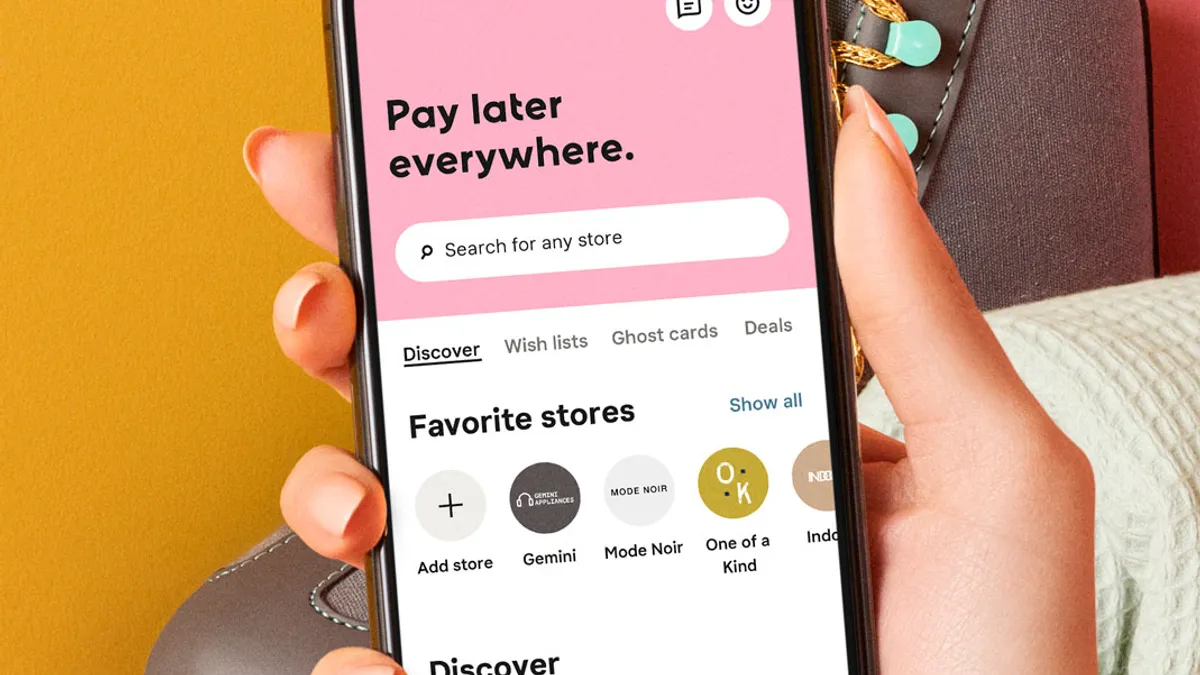

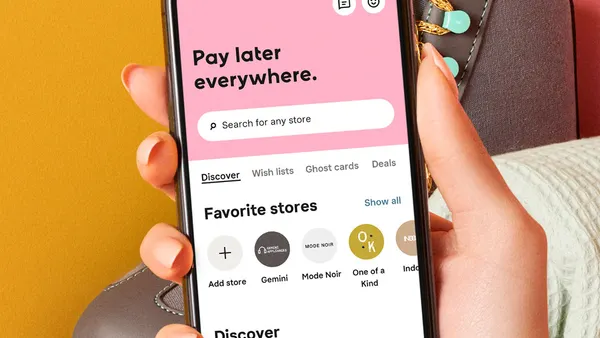

Leap has worked with a variety of brands — including Frankie’s Bikinis, Mack Weldon and Nisolo — to open retail locations, and has partnered with mall operator Simon Property Group. The retail platform works directly with landlords to secure leases for brands, in addition to helping them design and operate the omnichannel stores on Leap’s platform. Leap is paid a monthly operating fee by brands, as well as a percentage of sales.

In June, Leap announced that it raised $15 million in a funding round led by current investors BAM Elevate and Costanoa Ventures. Leap declined to provide comment to Retail Dive for this story.

Entering bankruptcy, Lunya hopes to right-size its balance sheet and confirm a reorganization plan.

Despite its financial and operational struggles, Lunya intends to continue “providing its customers with stylish, comfortable and affordable sleep apparel for years to come.”