Like so many department stores, Barneys launched about a century ago in New York City. But in 1923, when Barney Pressman pawned his wife's engagement ring to open his first location downtown, as the retailer's lore goes, it sold only men's apparel, at a discount.

It was Barney Pressman's son, Fred Pressman, who in the 1960s flipped the retailer to selling luxury instead, with the help of his friends Hubert de Givenchy and Pierre Cardin, making Barneys a destination for European men's fashion. (Fred Pressman also took away the apostrophe in the name.)

It wouldn't be until the 1970s, when the next generation of Pressmans expanded merchandise to include women's apparel and home goods, that Barneys had enough departments to call itself a department store.

Trends come and go, but institutions are timeless. pic.twitter.com/wjoX8eunjF

— Barneys New York (@BarneysNY) August 6, 2019

That may have been an achievement at the time, but "department store" hasn't exactly been a booming retail concept in the current landscape. Yet, Barneys largely escaped the stuffy reputation that has been increasingly visited on department stores in recent decades, as specialty retailers have stolen shoppers' attention and market share.

"Barneys was 'downtown cool,'" said Shawn Grain Carter, professor of fashion business management at the Fashion Institute of Technology who knew the Pressmans when she was a buyer at Bergdorf Goodman in the 1970s. "It’s a sad day. I was fearful that it would be Chapter 7 [a bankruptcy process that entails liquidation]."

Barneys is pretty close to that: While it is ostensibly restructuring under Chapter 11 as of Monday, it has until some time in October to find a buyer or liquidate. In documents filed with the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, Barneys said that it "has been operating without sufficient liquidity throughout the summer" and projected that it "will run out of money as early as next week without an immediate infusion of postpetition financing and access to cash collateral."

The company got a reprieve in the form of new additional financing on Wednesday, some $218 million from Brigade Capital Management LP and B. Riley Financial Inc. that will allow it to pay vendors and employees as it pursues a sale.

What happened?

Losing its cool

Barneys tried to maintain its cool. Earlier this year it opened "The High End," a luxury cannabis lifestyle shop, in its Beverly Hills flagship. And its "thedrop@barneys" immersive shop with food, workshops and installations has been offered in New York and Los Angeles in collaboration with streetwear brand Highsnobiety. The retailer also sponsors The Barneys Podcast, this season hosted by freelance journalist Noor Tagouri, which by its own description "features provocative conversations with boundary-pushing cultural leaders."

More broadly, the retailer has assiduously worked to present a fashion edit on the cutting edge, according to Thomai Serdari, a professor of luxury marketing and branding at New York University's Stern School of Business. But that has always appealed to a small slice of consumers, she told Retail Dive in an interview.

"It's very avant-garde, and that sort of avant-garde fashion needs a different type of consumer, which there aren't that many of anymore," she said. "It was sort of a three-dimensional glossy magazine, with a curatorial point of view and a very specific urban selection of apparel."

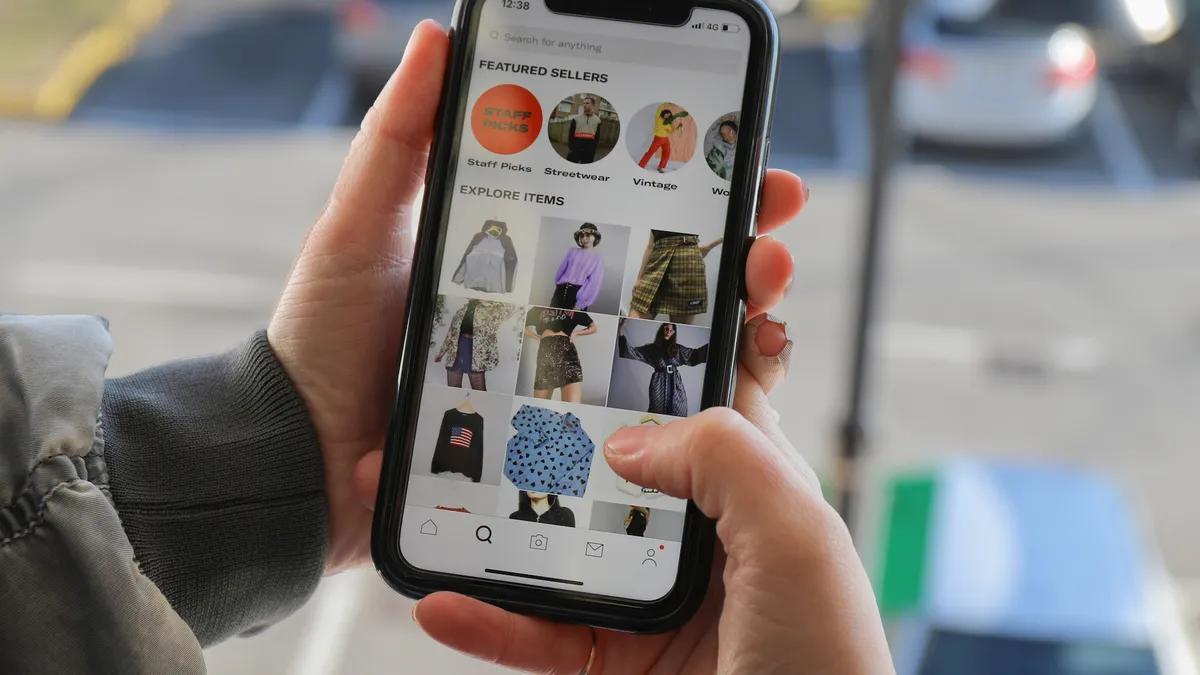

Carter agrees and said that the retailer failed to keep up with younger consumers and to reach them through today's requisite modes of marketing, like social media and influencers. "Physical stores are now really showrooms," she told Retail Dive in an interview. "Right now their fashion is geared mostly to the baby boomer. It’s great that their assortment is starting to shift to address that younger audience — but their marketing is not as successful."

Barneys stores are also in the wrong places, according to Carter. The retailer this week said it's shuttering most of them, including full-line stores in Chicago, Las Vegas and Seattle, along with five smaller concept stores and seven Barneys Warehouses. But the addresses of remaining stores don't have the edgy cachet once found at its downtown flagship, and their e-commerce and mobile commerce is inadequate, she said.

"Where is 'downtown cool' now?" Carter said. "It's Brooklyn! Even what used to be cool, the Lower East Side, is gentrified. Chelsea, gentrified. They were overstored and they were in the wrong markets. And now they're competing with Stitch Fix, Rent the Runway and Zara. They need to shift their approach. I think they have a chance if they can have consistent leadership and quickly build out their infrastructure to sell the majority of their products online."

Reaching millennials and Gen Z is more than having the right designs in the right locations, including online, however. Attention must be paid to the provenance of the merchandise and the way young fashionistas approach brands, according to Carter. "They are into a global understanding of what it means to be hip," she said "That means sustainability, that means they like farm to table food. Yeezy sneakers with an athleisure or streetwear attitude or gender-neutral attitude about apparel — and all of this is about social media."

Those younger consumers have finally turned their attention away from even the coolest department store, Serdari warned. "That younger population that could perhaps have been interested in Barneys, they have moved on to individual brands that have stand-alone stores," she said. "This marriage of high and low in luxury — young fashion consumers were four or five years old when that happened. Now we have Instagram, which is taking all the traffic away in terms of interest, in terms of where you get that avant-garde sense."

The rent is too high

This week's filing isn't Barneys' first bankruptcy rodeo. In its filing this week, the company notes that a 1996 restructuring under Chapter 11 was completed two years later.

In 2007, the retailer was taken over in a $942 million leveraged buyout by Dubai's state-owned investment firm. Most of the resulting debt load was erased in a debt-for-equity deal that turned over ownership in 2012 to investment firm Perry Capital. But Perry shut down in 2016, and its support since then, as it winds down, may have slowed.

Its current predicament is dire. "[A]dverse macro-trends as well as certain operational shortfalls ... More specifically, the general shift from brick-and-mortar retail has been further exacerbated by sharp increases in Barneys’ lease obligations, including over ten million dollars in rent increases on an annualized basis and corresponding letter of credit obligations, which severely decreased EBITDA and significantly constrained liquidity," according to documents filed Aug. 6 by Chief Restructuring Officer Mohsin Y. Meghji. "Due to these pressures, Barneys has been operating without sufficient liquidity throughout the summer of 2019."

"Challenging sales performance" from February to June sent revenue down by $34 million, according to the filing. The reference to rent comes just weeks after the retailer refuted reports that it would cut the space at its Madison Avenue store by more than half to save on rent, which reportedly doubled to $30 million (not including taxes and other costs) after arbitration with its landlord failed. But rent has also been an issue elsewhere: Each of the stores slated for closure has operated at a loss, together accounting for $14.2 million in losses last year, and would incur monthly rent of up to $2.2 million, Meghji wrote.

Barneys hasn't kept pace with operational change needed to stem such losses, yet it may have needed to pivot to omnichannel even more than rivals, Fitch senior director David Silverman noted in emailed comments following the Chapter 11 filing.

"Barney’s bankruptcy filing supports our views about omnichannel investments and the fashion cycle: scale has become critical given the rising costs of ominichannel investments to support customer loyalty and efficient operations, and fast fashion has grown in scale providing fashion-focused customers, who follow seasonal trends less, cheaper alternatives to luxury brands," he wrote. "Within luxury retail, Barneys’s revenue base of $800 million is well below that of Neiman Marcus, while Saks is part of Husdons Bay, which generated around $7 billion in revenue. Scale allows these competitors to invest significantly in long term growth initiatives around customer-facing elements like websites and store remodels, and infrastructure like robust supply chains. And because Barneys is a more fashion-focused department store than Neimans or Saks, it could have been more impacted by fashion cycle changes."

Expansion plans, for new locations in Florida's luxe Bal Harbour shopping center and the soon-to-open American Dream in New Jersey, a retail and entertainment spectacle from the owners of Mall of America, are unclear.

But even pursuing them was unwise, according to Columbia University Business School retail studies professor Mark Cohen.

"As for the deal they did at American Dream, even if free, which I’m sure it is — [that is] a crazy diversion of effort," he told Retail Dive in an email. "If the Madison Avenue landlord gives them a big break they might make a go of it. But that’s highly unlikely as the owner of the building refused to give them any relief last year and forced the matter into arbitration. Their New York fallback is the 17th Street store which I think they were foolish to open but now may become a lifeboat for them. At the end of the day, I think Barney’s isn’t going to get well any time soon."

Kaarin Vembar contributed to this report.