Amazon is pulling back the curtain on how it’s teeing up more packages to arrive on doorsteps without Amazon logos. Last week, the Ships in Product Packaging program expanded by opening participation to hundreds of thousands of sellers in the U.S. and Canada that use Fulfillment by Amazon.

Amazon itself had already been increasing the amount of items it ships without additional Amazon packaging, and the e-commerce giant announced last year that sellers would be able to join its SIPP program in 2024.

It ran a pilot program with a small group of selling partners in 2023 to learn what information sellers needed to fully understand SIPP and enroll a product. The pilot “helped us develop what is a really scalable way to provide information to sellers,” said Kayla Fenton, senior manager of packaging innovation at Amazon.

Sellers are a diverse group, Fenton said: “They have a range of interests in what’s important to them — whether that be fee incentives or customer experience or sustainability — but they also have a range of experience, especially as it relates to packaging.”

Less packaging, more savings

The SIPP push is one of Amazon’s recent packaging changes to improve company sustainability. Amazon announced last year that it would phase out plastic mailers, and it upgraded the technology at a fulfillment center in Ohio to make it the company’s first to handle fiber packaging alone — no plastic. Amazon is working to lightweight its packaging and ultimately “eliminate packaging altogether.”

Sellers who enroll in the SIPP program will receive discounts. Savings will be based on the existing FBA fee tiers — which primarily consider package size and weight — but generally they will range from 4 cents to $1.32 per unit. Even if a consumer specifically opts in during checkout to add Amazon packaging for shipment, a seller participating in SIPP will still receive their discount, Fenton said.

The level of incentives vary because “if you're avoiding adding a very large overbox to a product like a ... kitchen appliance, that's different both for the seller and for Amazon than if you're avoiding an additional package for a T-shirt that might be pretty small and also be shipping in a pretty compact package today,” she said.

Amazon previously reported that it shipped 11% of products in their own packaging in 2022. The company isn’t releasing an expectation for how that figure could grow in light of the expansion, or how many sellers currently participate in SIPP. But it’s “certainly anticipating that it increases over time,” and the company is eagerly watching this year’s adoption rate, Fenton said.

Which products make the cut?

While Amazon currently has about 2 million independent sellers worldwide, for now SIPP only is being offered for those in the U.S. or Canada, and they must be part of Fulfillment by Amazon, in which Amazon takes care of packaging for a seller’s products.

Sellers also must ensure their products meet eligibility criteria to ship without additional packaging. Size is the biggest determinant: Amazon won’t ship small products in their own packaging for numerous reasons, including the inability to put labels on them.

Other determining factors for SIPP approval include product weight or sensitivity factors. Amazon says all criteria are clarified to sellers in an online hub, Seller Central.

“At the end of the day, our first goal is to make sure that the product arrives to customers undamaged,” Fenton said. “Meeting the testing requirements is the last piece of the puzzle for a product to be enrolled.”

Products can be tested in a variety of ways, and Amazon receives the final report. Following testing, Amazon can certify a product as eligible for SIPP or recommend changes to meet program criteria.

“One seller might have to make a very minor change in order to meet our eligibility criteria. Other sellers might have to sort of think about their packaging in a bigger way and maybe sort of change the format altogether to meet standards,” Fenton said.

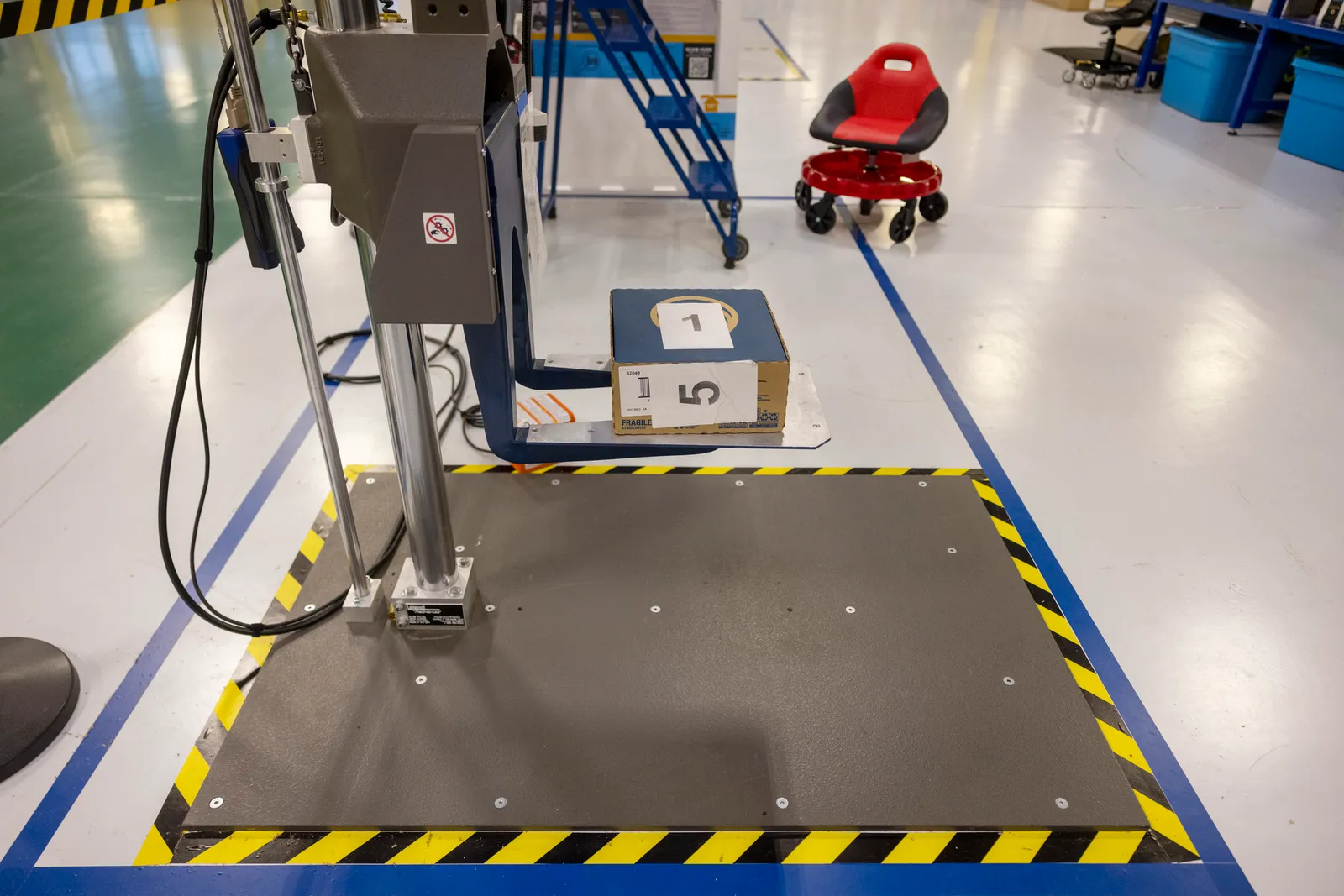

Some of the work to certify sellers’ products for SIPP lies inside Amazon’s Packaging Innovation Lab in Sumner, Washington. That’s the primary site for packaging innovation and testing, although some work also occurs in other locations, including third-party labs.

“Every one of these interactions with the selling partner, on the other end is one of our lab technicians. So [the sellers] are talking to people that actually know about packaging and have seen, in some cases, thousands of different items get tested,” said Josh Samples, senior manager on the packaging innovation team. “We try to give specific answers that can help them get to their certifications.”

He explained that working with such a wide variety of sellers, from big companies to mom-and-pop businesses, results in Amazon gathering scores of information from which technicians can develop customized recommendations, rather than employing a one-size-fits-all approach. The team looks for ways to improve the seller experience and speed up the SIPP onboarding process, such as by recommending that fewer items are tested if they can be grouped together for certification.

“We've had instances [where] a seller submits a bunch of different tests and test reports, when we can say, ‘Hey, actually, these are all really similar. You don't need to test every different color of a T-shirt,’” Samples said. That being said, the lab does not compare one seller’s products to another seller’s. “We wouldn't want to make inferences and say, ‘You know, what we've learned from Seller B is that T-shirts do this, and so you don't want to do it.’ We kind of assume for every single seller they're unique,” he said.

SIPP spurs creative packaging formats

One example of working with a customer on a SIPP-ready product is Amazon’s partnership with Procter & Gamble on Tide detergent packaging. The partners decided to convert the liquid-holding plastic jugs to a bag-in-box design so the product could ship in its own packaging. Compared with the jugs, the revamped packaging also includes 60% less plastic and is four pounds lighter.

Despite potential efficiency benefits from grouping similar items, Amazon does more robust testing for certain products, such as fragile items. “We try to find ways to use our capacities in the lab to help get those items [certified] and make sure that we put a real scrutinous eye on them,” Samples said.

Testing at the lab typically involves “a series of drops and vibrations,” but the methods and machines used are determined by product type, he explained.

“We might, for example, want to understand how a large palletized item would perform when a truck comes to a screeching halt. That's not something we're going to think about for a T-shirt,” Samples said.

This year and beyond, Amazon aims to continuously improve the seller enrollment process for SIPP, although sources wouldn’t provide details on specific steps.

“We're changing our fulfillment network every day ... using science and data to try to understand — as Amazon is building out this network and it's evolving, what should that mean about our test methods?” Samples said. “If you were to come back and ask that question three years from now, we might have totally different test methods.”